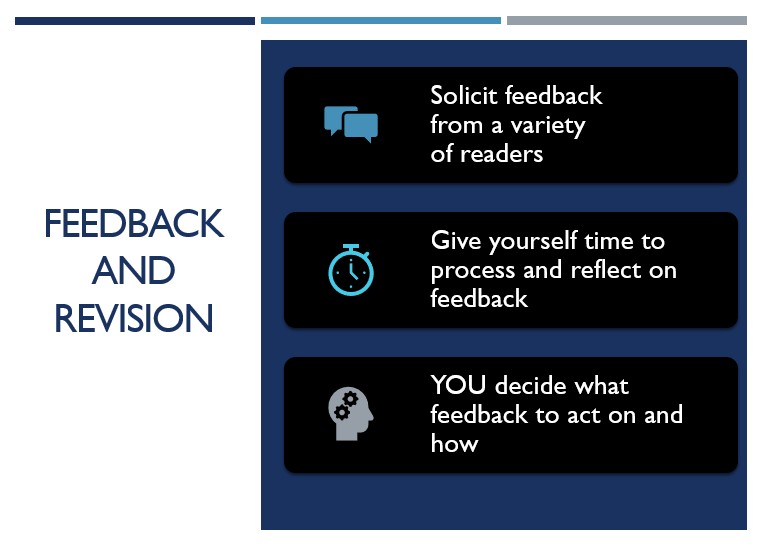

When you get negative feedback, give yourself time to process it. Be open to suggestions and making changes, but also reflect critically. Use your support system to help you process, understand, and emotionally deal with feedback and revision.

Processing & Integrating Critical Feedback

When writers receive critical feedback, they commonly move through several common stages: an immediate emotional response of denial, anger, or frustration; rationalization (“They just didn’t read this right”); acceptance; and action. While having an emotional response is a normal reaction, it can also be stymying and lead to writer’s block. You can move toward productive action more quickly by:

- Taking all the feedback in

- Identifying what you’re feeling

- Seeking a supportive environment

- Asking questions for clarification

- Making an action plan

- Keeping a feedback log

Negative Feedback from Advisors

If you regularly receive critical or overwhelming feedback from your advisor, consider taking one of three approaches to the situation:

Approach #1: Talk to your advisor about the kind of feedback you find most productive at different stages in the writing process. You might practice writing a feedback request note that includes:

- A summary of your paper’s or chapter’s argument and how it fits into the larger dissertation

- What stage the writing is in

- A prioritized feedback list detailing the type of feedback you’d like

- Optionally, an indication of what you feel is a weakness and/or what you’d like the reader to ignore in the draft. For instance, most early-stage writing benefits most from feedback on macro-level issues (structure, argument, contribution, analysis) rather than fine-grained editing.

Approach #2: If talking with your advisor isn’t a possibility, consider switching advisors or exploring the possibility of co-advising. If you choose to change your advisor, be sure to have another professor willing to step in. Focus on moving on rather than critiquing your advisor’s style.

Approach #3: If neither of these options is feasible, find other sources of positive feedback. This could be other committee members or colleagues, members of a writing group, or writing center consultants. The University of Illinois Thesis Office also offers resources for working with difficult mentors.

Negative Feedback from Reviewers

It’s easy to feel intimidated, depressed, or blocked by having a manuscript or proposal rejected. However, be aware that many factors can influence your critics’ judgment of your work: the reviewers’ level of interest in your project, the extent to which they feel your work intrudes on their disciplinary territory, their perception of your persona or knowledge, or problems in their own personal lives. One interesting study (Fishe and Fogg, 1990) analyzed 402 reviews of 153 papers submitted to American Association journals and concluded, “In the typical case, two reviews of the same paper had no critical point in common.”

So, while you have every right to be upset by rejection, there’s likely no reason to abandon your manuscript: look for patterns in your reviews, be selective about which comments you accept and reject, and send it out again. Persevere, and keep that momentum going!